Josh

According to Article XIV of the Philippines’ 1987 Constitution,

Section 6. The national language of the Philippines is Filipino.”

Section 7. For purposes of communication and instruction, the official languages of the Philippines are Filipino and, until otherwise provided by law, English. (Belvez, 2015).

Since the establishment of the Philippines as a bilingual nation, English has surpassed its intended role of “communication and instruction.” With growing pressure from society and the government to strengthen its use, English has become the language of controlling domains over the years (Borlongan, 2009). The video above simply highlights how English is no longer only used by Filipinos in formal contexts and that it has penetrated society, to the point where many Filipinos (at least those from the mainland) are no longer able to speak “pure Filipino.”

As a Filipino immigrant, I’m interested in examining how the nation’s history of being colonized by the United States has affected how Filipinos living in the Philippines use and perceive these languages. Furthermore, I want to look at how these attitudes affect Filipinos who migrate to the U.S. and influence the formation of their first-generation US-born offspring’s Filipino identities.

How Does the Philippines View the English Language and American Culture?

In a video that went viral in the Philippines, which was taken from TLC’s show “90-day Engagement,” we meet a girl from Urdaneta City, Philippines. My interest is not on her engagement but more on the public response to the her English-speaking skills. More specifically, I was fascinated by the way people criticized her in the comments.

Her mispronunciation of the sentence “you’re rude” to “you’re ROAD” became a sudden Internet meme. Interestingly, the majority of the people mocking her English were Filipino natives, all of who are well aware of the quality of the English curricula in many poor provincial schools. For some reason, there’s this mentality among Filipinos that speaking English with even the slightest accent, no matter how proper one’s grammar might be, equals to being poor or uneducated and thus deserving of ridicule.

This video was of specific interest to me because it reflected the insecurity Filipino immigrants have with regards to their cultural identity, finding comfort in their efforts to achieve “American-ness.” Being previously occupied by the United States, the affection towards western culture and/or Eurocentric ideologies favors a hierarchical distinction between the Filipino and the English languages, with Filipino being the inferior. Influenced by our past as a colonized nation, many Filipinos see the English language as a tool that they could use to advance their social status in the Philippines. History places them/us under the impression that the mastery of the English language is equivalent to social and economic mobility. In my interview with Sam Ng about her experience as a child of an immigrant, she claims that maintaining this sort of mindset “ is extremely detrimental to a Filipinx’s use of native tongue and ancestral identity because we internalize our community’s oppression! And by denouncing your native tongue, you are only silencing your voice as a Filipinx/Asian American.”

Filipino Migration and Chasing the American Dream

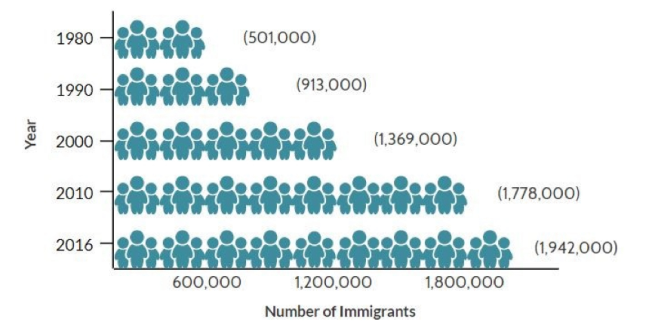

The history of Filipino migration to the United States traces all the way to the late 19th century and has fluctuated ever since. The United States first saw a huge influx of Filipino immigrants after the country annexed the Philippines in 1899. The Filipino people would remain under American rule up until 1946, which is when the country was finally granted it’s full independence. During this period of American imperialism, many Filipinos travelled to the United States to either study or work (Figure 1).

The valorization of the English language is only one of the ways by which the Filipino desire to be “American” is reflected. The United States has always been seen as a symbol of hope and opportunity for the Philippines. Today, many people move to the U.S. in hopes of pursuing the “American Dream,” a mentality that is heavily rooted in the country’s once dependence on the U.S. As many Filipino parents will learn, however, moving might open up opportunities for their children but with it comes an insecure sense of detachment from their Filipino identity as a function of so-called “language barriers.”

The Language Barrier and The Reluctance of Parents to Teach Children Their Native Tongue

Taking a close look at the present Filipino and Filipino-American cultures can provide deep insight into the long lasting effects of American colonialism on the Filipino identity.

In an interview for KQED News, Dominic Lim, a first-generation Filipino-American, talks about how growing up surrounded by Filipino food, music & other aspects of the culture, but not knowing how to speak the language left him feeling like his Filipino identity was incomplete (Guevarra, 2016).

“I always thought that the language component [of one’s own racial identity] was sort of the one piece that I was lacking.” -Dominic Lim (KQED News, 2016).

In my personal research, I asked some friends who were born here in the U.S. but whose parents migrated from the Philippines about their experiences growing up. My focus was to understand whether this feeling of personal detachment constructed by the language barrier from their Filipino-speaking families is shared among many first generation Filipino-Americans. True enough; many of them expressed how challenging it was trying to communicate with their parents and with their extended family members during family gatherings. One of my friends explains that the reason her parents never taught her Tagalog (a Filipino dialect) was the fear that developing an accent would only attract discrimination.

“My parents never raised me to speak Tagalog, yet they always spoke to each other in [it]. When I asked my mom why she never taught me a second language, she said she did not want me to get bullied in school if I had an accent since I went to private, predominantly white schools.” -Tala

David Lim’s mother, Consuelo Tokita, was quoted giving the same reasoning for her hesitation to impart her language to her son. Her unwillingness, however, was more personal, as it stemmed from her own experience struggling to find a job in the United States because of her accent. Their testimonies provide evidence to the reluctance that many Filipino immigrant parents have when it comes to teaching their children their native language. By choosing to teach English over the language they themselves grew up with, immigrant parents not only permit sociopolitical and state structures to further oppress and marginalize native tongues, but they also further perpetuate the denial of their own language as a whole.

References

Belvez, P. M. (2015, April 29). Development of Filipino, The National Language of the

Philippines. Retrieved from http://ncca.gov.ph/subcommissions/subcommission-on-cultural-disseminationscd/language-and-translation/development-of-filipino-the-national-language-of-the-philippines/

Borlongan, A. M. (2009). A Survey on Language Use, Attitudes, and Identity in Relation to Philippine English among Young Generation Filipinos: An Initial Sample from a Private University. Online Submission, 3, 74-107.

Guevarra, E. (2016, February 27). For Some Filipino-Americans, Language BarriersLeave Culture Lost in Translation. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from https://www.kqed.org/news/10746111

Zong, J., Zong, J. B., & Batalova, J. (2018, March 29). Filipino Immigrants in the United States. Retrieved April 19, 2018, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/filipino-immigrants-united-states